Evaluating the money saved by digitizing salary payments

By Zach Andersson, Acting Project Director, LIFT 2. This post originally ran here on the mSTAR blog.

Funded by USAID and led by FHI 360, mSTAR/Liberia ended activities in May 2018 after enrolling 4,870 civil servants across Liberia into mobile salary payments and successfully handing the mobile salary payment program over to the government. This post is part of a summer blog series on mSTAR/Liberia: what went well and why, how we overcame challenges, and lessons for the future.

Exactly how much could government ministries save by digitizing salary payments? In Liberia, we do the math to find out.

The Government of Liberia, like many governments in developing economies, faces resource constraints which affect public service delivery. With an annual budget of $526 million, the lack of capital is evident across the country, from poor road quality to broken down ambulances.

Difficulties like bad roads, a lack of banks and low liquidity lead health and education workers to leave their shifts for hours and even days to pick up their salaries. From 2016 – 2018, mSTAR worked with Ministry of Health (MOH) and Ministry of Education (MOE) to digitize their workers’ salaries. We believed digital payments could not only save staff time and money spent when traveling to a brick-and-mortar bank each month, but could also keep workers from leaving work to do so. We collected data over the course of the two-year project to assess our progress and pivot, as required, to achieve high satisfaction of salary recipients and create a successful, sustainable system.

Standard survey tools developed and implemented by the mSTAR team demonstrated that when picking up salaries from mobile money agents instead of banks, health and education workers reduced the amount of money they spent by 58 percent and decreased the amount of time missed from their jobs by an average of 12 hours per month.

Going beyond the benefit of mobile money salaries for individuals, mSTAR sought to estimate the monetary value of the productivity lost when staff left work to collect their salaries each month.

How did we do this?

1. The first step was calculating the total self-reported hours missed away from work when collecting salaries via mobile money and direct deposit at the bank by the 194 MOE and 222 MOH staff surveyed. Using assumptions for both ministries of an eight-hour workday, five-day work week and four-week work month, the total number of possible hours per month MOE and MOH could spend on the job was also calculated (160). Keep in mind that banks have restrictive hours (normally 9am-2pm), whereas with mobile money there is more flexibility. Mobile money agents set their own schedules and usually are available after work, which allows health and education staff to remain on the job longer rather than leave their work to collect their pay.

2. With ministry survey samples for both the total hours missed collecting salaries via mobile money and direct deposit, a proportion of all possible work time missed was calculated. To do this, mSTAR aggregated the reported time missed away from work by staff surveyed and converted to hours, then divided by the total number of hours all those staff together could have worked. For the education sample, this came to 0.6 percent through mobile money and 10.9 percent through direct deposit, whereas for health, these were 0.7 percent and 5.9 percent respectively.

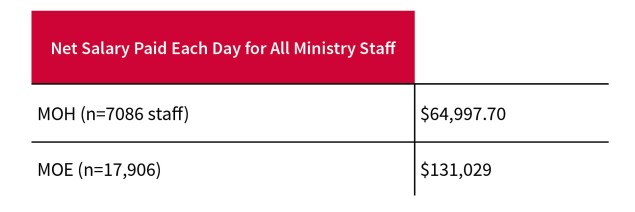

3. Referencing a UNCDF High Volume Payments Mapping presentation given June 28, 2017, we calculated the net salary paid for all staff each day.

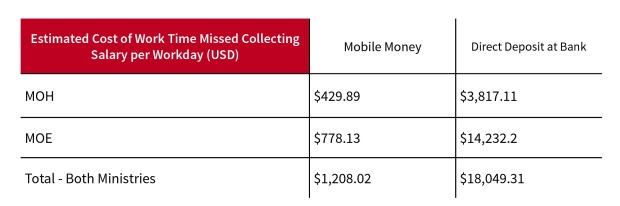

4. We then estimated the “cost” to both Ministries in terms of lost productivity resulting from staff absence from work to collect their salaries. We multiplied the net salary totals for the entire population by the proportions of all possible work time missed by staff surveyed (step #2 above).

4. We then estimated the “cost” to both Ministries in terms of lost productivity resulting from staff absence from work to collect their salaries. We multiplied the net salary totals for the entire population by the proportions of all possible work time missed by staff surveyed (step #2 above).

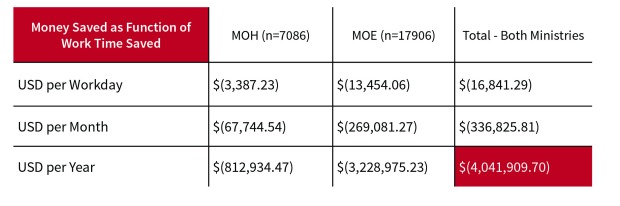

5. Subtracting the mobile money estimated costs of work time missed from the direct deposit estimated costs, the total estimated savings for both Ministries are presented below by workday, work month and work year.

5. Subtracting the mobile money estimated costs of work time missed from the direct deposit estimated costs, the total estimated savings for both Ministries are presented below by workday, work month and work year.

So, what does this mean?

If all MOH and MOE staff transitioned to mobile salary payments, the government could potentially save around $4 million – the estimated value of the productive work time lost due to staff leaving their jobs to collect their pay.

While the findings provide food for thought for Government, there are a few critical limitations to keep in mind. The proportion of all staff surveyed by mSTAR from both ministries is small – only 3.1 percent of the MOH and 1.1 percent of the MOE. mSTAR cannot say with certainty that the staff surveyed are representative of the wider MOE and MOH populations. Staff surveyed by mSTAR opted into the mobile money salary payment – many other staff chose not to join. Therefore, surveyed staff may be predisposed to missing less time from work than others who have not yet joined (i.e. the rest of the ministry populations), which may reduce the utility of the multipliers.

The Government of Liberia seemed to take these results seriously. At the project closeout event in front of a large audience and media, the Director of Pay, Benefits and Pension at the Civil Service Agency, Roland Kallon, spoke of mobile money as the way of the future. Referencing the savings, he said, “mobile money process is what everyone should be gearing toward because it makes a lot sense…if you compare mobile money with any other mode of payment, anyone will choose mobile money.”

Zach Andersson is a Monitoring and Evaluation Advisor at FHI 360 and an Acting Project Director for FHI 360’s Livelihood and Food Security Technical Assistance (LIFT II) project. Zach has over 10 years of experience in disaster relief and global development program design, operational oversight, research, M&E and information management, proposal development, and technical assistance with successful, extended field deployments to Uganda, Ghana, Haiti, India, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi and Tanzania. He has produced and administered surveys, facilitated training and workshops, created assessment tools, edited and published guidance documents, built and maintained relationships with government and bilateral stakeholders, led research activities, and collaborated in the development of M&E indicators for disaster relief, economic strengthening and HIV work in several separate roles.

You might also like

-

Hands on with GenAI: predictions and observations from The MERL Tech Initiative and Oxford Policy Management’s ICT4D Training Day

-

When Might We Use AI for Evaluation Purposes? A discussion with New Directions for Evaluation (NDE) authors

-

A visual guide to today’s GenAI landscape

-

Register now for the NLP-CoP Ethics and Governance Working Group Meeting on April 18th