Data Governance in the African Context

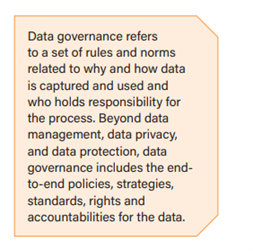

Data governance aims to increase the value of data, minimise data related costs and risk, and offer a cross functional framework for managing data.

Dominant data governance models have been established by the so-called ‘Big Tech’ monopolies based largely in the United States, China and the EU, to meet their business and financial interests.

These models have been subject to increasing criticism for advancing values and practices that serve their own benefits and result in harm for the individuals and groups who rely on these technologies and to entire societies.

References to ‘data as the new oil’ have led many to question how data is governed on the African continent, who extracts and processes the data of Africans, and who derives value from that data.

Data legislation in Africa

Since the emergence of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016, countries around the world have developed their own national data bills, acts, laws, and regulations.

As of 2021, twenty-eight African countries had passed data protection laws — the most recent being Uganda, Kenya and Egypt. Other countries, including Nigeria, have introduced data protection bills which are at various levels in the respective country legislative agendas. Most of these emerging African data protection laws are modeled after the GDPR, using similar language and principles.

Regional data protection on the African continent has been strengthened over the past decade. In 2010, for example, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adopted a Supplementary Act on Personal Data Protection. In 2013, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) published a Model Data Protection Act, and in 2014 the African Union adopted the Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (the Malabo Convention), which is a comprehensive document covering electronic transactions, privacy, and cybersecurity.

Commonalities among African data protection frameworks and statutes include:

- The acts/bills apply to the collection, storage, processing and use of personal data relating to persons living in their country and persons of their nationality, and to entities that are registered and operating in these countries. Foreign entities targeting persons living in the country must also follow these laws.

- Consent of data subjects for data collection and processing is also mandated in these frameworks. Basic principles relating to processing of personal data, such as the right for an individual to know what data has been collected about them over what period of time; how much of their data has been captured or processed; what it is being used for; the right to refuse data collection or processing; the right to withdraw consent for data processing; the right to request deletion of their personal data; and the right to prevent their data from being shared with third parties without consent. A data controller must have proof that the data subject has consented to the processing of their personal data and must not coerce consent or force data collection in exchange for access to services or information.

- Establishment of a data protection commission is required. It must be led by a data protection commissioner who oversees the implementation and enforcement of the data protection act. The data protection commissioner enforces penalties and fines for anyone found responsible for the improper use of data or data breaches.

- These frameworks also embody basic privacy principles, including collecting data only for a specific purpose; limiting the amount of data that is collected; accountability; limiting the duration for which data can be stored; transparency; confidentiality; and capturing data as accurately as possible.

What about community-centered data governance frameworks?

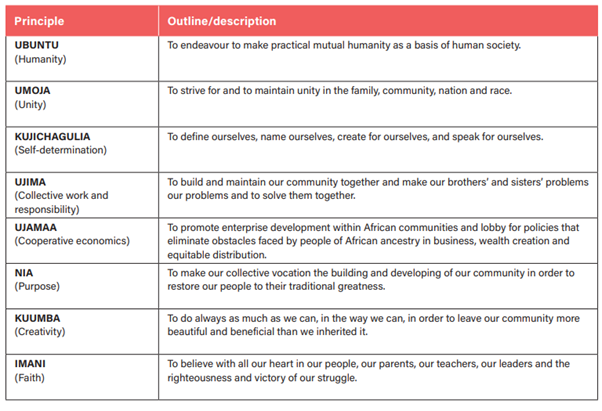

An emerging framework for data governance seeks to offer a different model for data protection in contexts – such as those in African nations – that do not match that of the EU. Instead of focusing on personal data, this framework places the collective interests of communities and their aggregate data at the centre. Data is considered an extension of a community itself. In the African context, for example, in addition to principles like transparency, accountability, responsiveness, and sustainability, existing home-grown principles are proposed that articulate and speak to a spirit of collectiveness and that serve as an organizing unit in most communities. (See seven principles of Kwanza)

African principles that could help to frame context-relevant approaches to data governance:

In addition, the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance set up by the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (inspired by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) reaffirms local communities’ rights to self-governance and authority to control their cultural heritage embedded in their data and is more aligned to emerging models.

In this regard, attention turns to the practices for data access and control developed by data stakeholders. Third parties seeking to appropriate community data are required to ensure safeguards through mechanisms such as data trusts, data pools or other data sharing arrangements that are fit for the developing south and that help to guarantee greater local control and decision over data.

The core principles of CARE:

Let us know about emerging data governance in your part of the world, and how this has influenced your M&E work! Let’s seal the discussion in our next post as we discuss Data governance and M&E.

Read more about Data Governance in the African Context in Part 1 of the Responsible Data in Monitoring and Evaluation paper. To follow the series, check our previous blog posts: How is the data revolution influencing digital MERL in Africa? ; MERL and the African Data Ecosystem; and Data Rights as Human Rights

You might also like

-

Join the AI and African Evaluation Working Group Meet ‘n’ Mix Session on May 7!

-

Hands on with GenAI: predictions and observations from The MERL Tech Initiative and Oxford Policy Management’s ICT4D Training Day

-

When Might We Use AI for Evaluation Purposes? A discussion with New Directions for Evaluation (NDE) authors

-

A visual guide to today’s GenAI landscape