MERL and the African Data Ecosystem

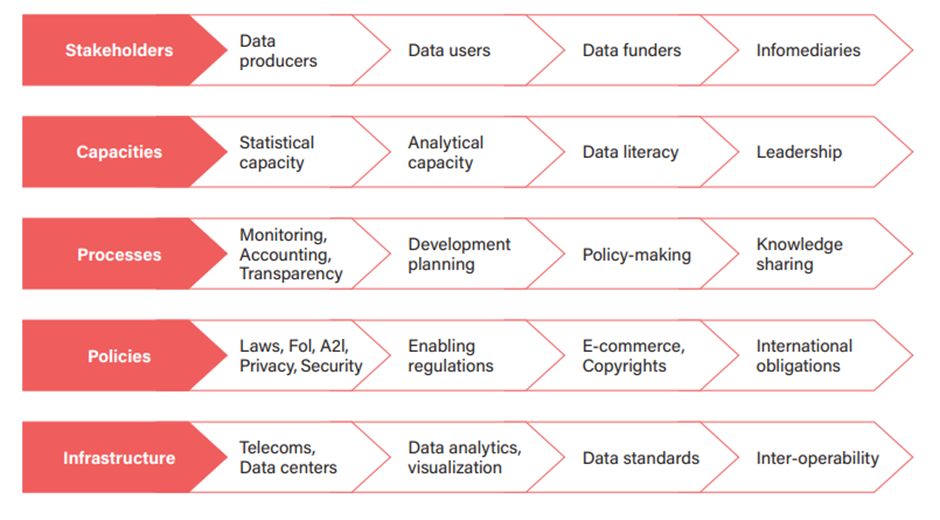

The term ‘data ecosystem’ describes the complex web of relationships between individuals, organisations, datasets, standards, resources, platforms, and other elements that define the environment in which a data resource exists. (See the Open Data Charter and the Africa Data Consensus for more on data ecosystems).

A data ecosystem encompasses multiple data communities where people, processes, technology, and culture all play a role in data governance, as noted by Buttles-Valdez and team.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) illustrates the key stakeholders and their roles in the data ecosystem as follows

National Statistical Systems and New Data Actors

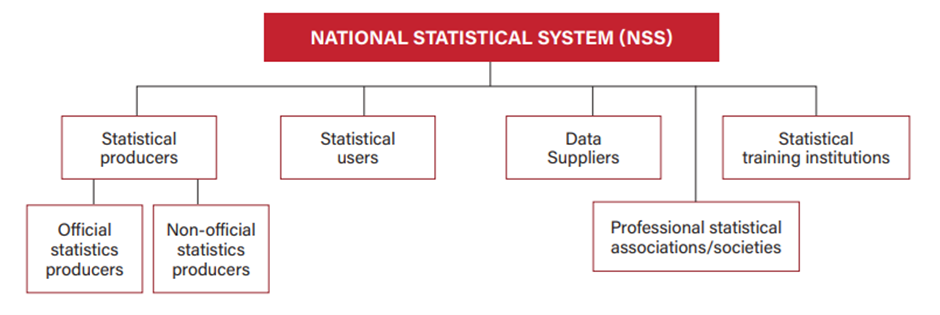

In the African data ecosystem in particular, it is important to consider the role of National Statistical Systems (NSS) within the data ecosystem. Many NSS focus only on producing official statistics, with the head of the National Statistics Office (NSO) leading the NSS. This omission of important data and other statistical activities conducted by non-state actors, including M&E practitioners, starves countries of vital information that could support with planning, allocation of resources, and other aspects of governance.

in 2016, Msokwa advocated for the inclusion of other actors into NSS structure as follows

In this case, the NSO would coordinate the entire NSS, including both official and non-official data sources. This could enable greater collaboration – in data collection, data processing, analysis, dissemination, and storage. It could help to fill gaps in the NSS and enhance data accessibility, dissemination, and use, as noted by the UNDP. Advances in ICT have opened the data ecosystem in many African countries to include non-state data producers, for examples, see Citizen generated data in Kenya: a practical guide.

Expanded roles and growing pressures

To take on an expanded role, NSOs would need to increase their capacity. And challenges have already been identified, for example, government and corporate surveillance, data privacy and security. While anonymisation has been a key technique for sanitising datasets and enabling open access to data, advances in computing and technology have made the deanonymisation of individual data increasingly possible, making data anonymisation is no longer enough to protect privacy (See Rocher and team).

Furthermore, the positions of state and non-state actors may not align when it comes to reporting on 1) The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); 2) The Open Government Partnership (OGP) platforms; and 3) The continental African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) which is a self-monitoring mechanism aimed at promoting good governance.

This has put increased pressure on NSOs as key stakeholders within the broader NSS, forcing them to take the lead in navigating a new set of challenges, as noted in the African Governance report. In addition to greater protection for personal, sensitive and anonymized data, proper redress is needed for cases where data is misused or transparency and accountability are missing. Anyone working with data needs to be sensitive to these issues.

Unequal power dynamics

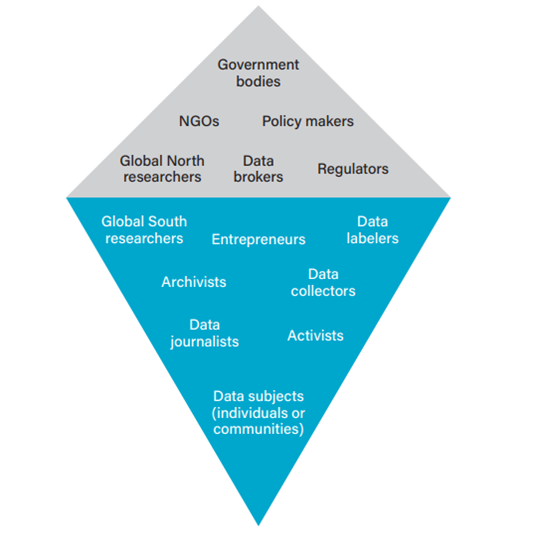

Whereas data sharing can support research and policy design to help alleviate poverty and inequality, there is growing disquiet around the fact that datasets are often extracted from African communities who do not reap the same benefits as those who collect the data or those who own the data infrastructures (see Abebe et al, 2021).

According to UNDP unequal power relations inherent in the data ecosystem undermine citizens’ rights to control their data – this includes disrespect for traditional values of local communities in the collection and use of data. In addition, debates around the challenges of data collection, use and sharing in Africa are too often driven by non-African stakeholders.

Abebe et al, in 2021 illustrate this in a more holistic depiction of the African data ecosystem, where those at the top of the iceberg wield more power and influence than the individuals at the bottom, who remain ‘hidden’.

As outlined in Part 1 of the guidance on responsible data governance, a standardized approach to data governance will not benefit all African countries equally. Even those countries with similar colonial histories will need to ensure that their data governance models are fully contextualized.

The question therefore becomes: how can Africa maximize the benefits of the data revolution while minimizing the risks?

Let us know what you think, and join us again in the next post as we discuss Data rights as Human rights.

Leave a Reply

You might also like

-

What’s happening with GenAI Ethics and Governance?

-

Join the AI and African Evaluation Working Group Meet ‘n’ Mix Session on May 7!

-

Hands on with GenAI: predictions and observations from The MERL Tech Initiative and Oxford Policy Management’s ICT4D Training Day

-

When Might We Use AI for Evaluation Purposes? A discussion with New Directions for Evaluation (NDE) authors

I have been in the data production business in developing countries for decades. Each year, we the producers search for more efficient ways to produce data. While all the efforts are sincere and laudable, we have somehow managed to ignore addressing the real challenge– which lies on the demand side. Some continue to make passionate arguments about how things are changing–perhaps based on some small study or particular positive situation in one community. Yes, people in the government will often bemoan the lack of data. But how badly do they really want to use that data? I think the below questions need to be posed and answered comprehensively before any data collection is done in these developing country environments.

1. Which offices need the data?

2. Among the offices that need the data, which ones will actually use it?

3. What will they use it for?

4. Do they have qualified staffs who can analyze, interpret and apply the results as intended?

5. What influence do they have in the office or government? (this is important because if the decision maker does not like the results, it may be ignored)

6. If the data exists but not used, what is the penalty to the decision maker?

In brief, I think we data producers need to all focus only on the accountability dimension in government and the issue of data use, data demand, data quality, statistical productivity and even higher salaries at the NSOs would begin to improve in a meaningful way.

5. How have they been operating or making those decisions before?

6. Why do you think they will change?